Challenges

To quickly review: Social Security is a federal social insurance program financed entirely through a trust fund that…

- Receives money from a dedicated revenue stream - a payroll tax; and

- Provides the money for benefit checks sent to retirees.

Because of this trust fund, Social Security is unique when compared to other government programs.

From its inception, the program has operated under a political agreement that set the following conditions:

- The trust fund’s main source of revenue must be payroll taxes; and

- The trust fund can only pay out benefits that are covered by its revenue.

But this unique structure also carries some unique challenges.

PAY-AS-YOU-GO

While your payroll taxes fund the Social Security program, that money isn’t set aside for your retirement. Instead, the Social Security Administration uses your taxes to send monthly checks to current retirees.

Social Security is a pay-as-you-go system. And to keep it up and running, we need enough workers paying into the program, so it can send benefits out to retirees.

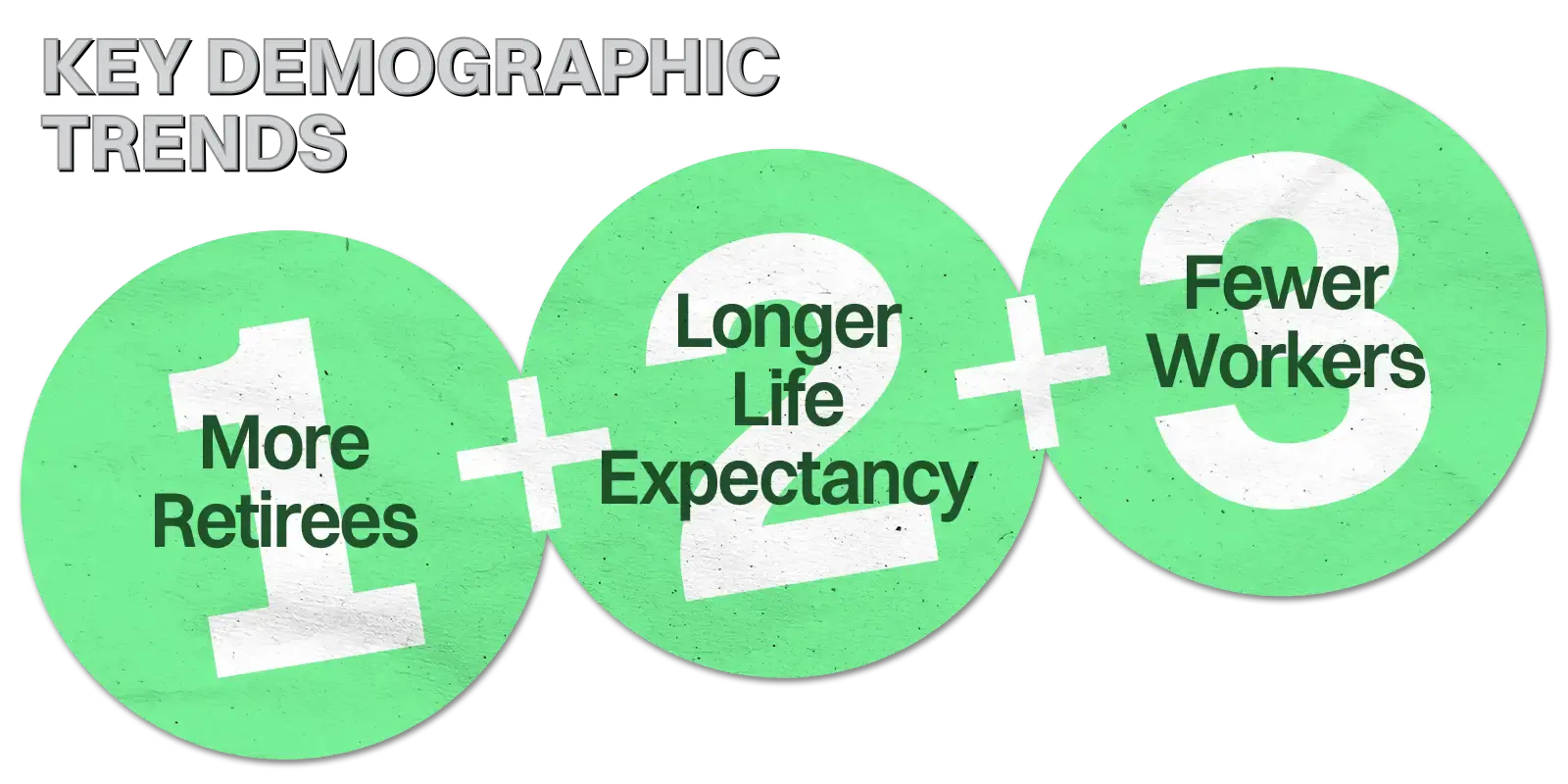

The problem is that Social Security’s pay-as-you-go funding structure makes it vulnerable to certain demographic trends.

In recent years, changes in the number of U.S. workers, the number of retirees, and our average life expectancy have created real problems for the program’s long-term solvency and stability.

MORE RETIREES, LONGER LIVES

When Social Security first started sending out monthly checks in 1940, less than 250,000 Americans were eligible for the program. In 2023, 58.6 million received old-age or survivors insurance from Social Security. And enrollment in the program is expected to grow as more Baby Boomers reach the age of eligibility.

Born between 1946 and 1964, more than 65 million members of the Baby Boomer generation are alive today. This group began reaching retirement age in 2011, and all of them will be 65 or older by the year 2030.

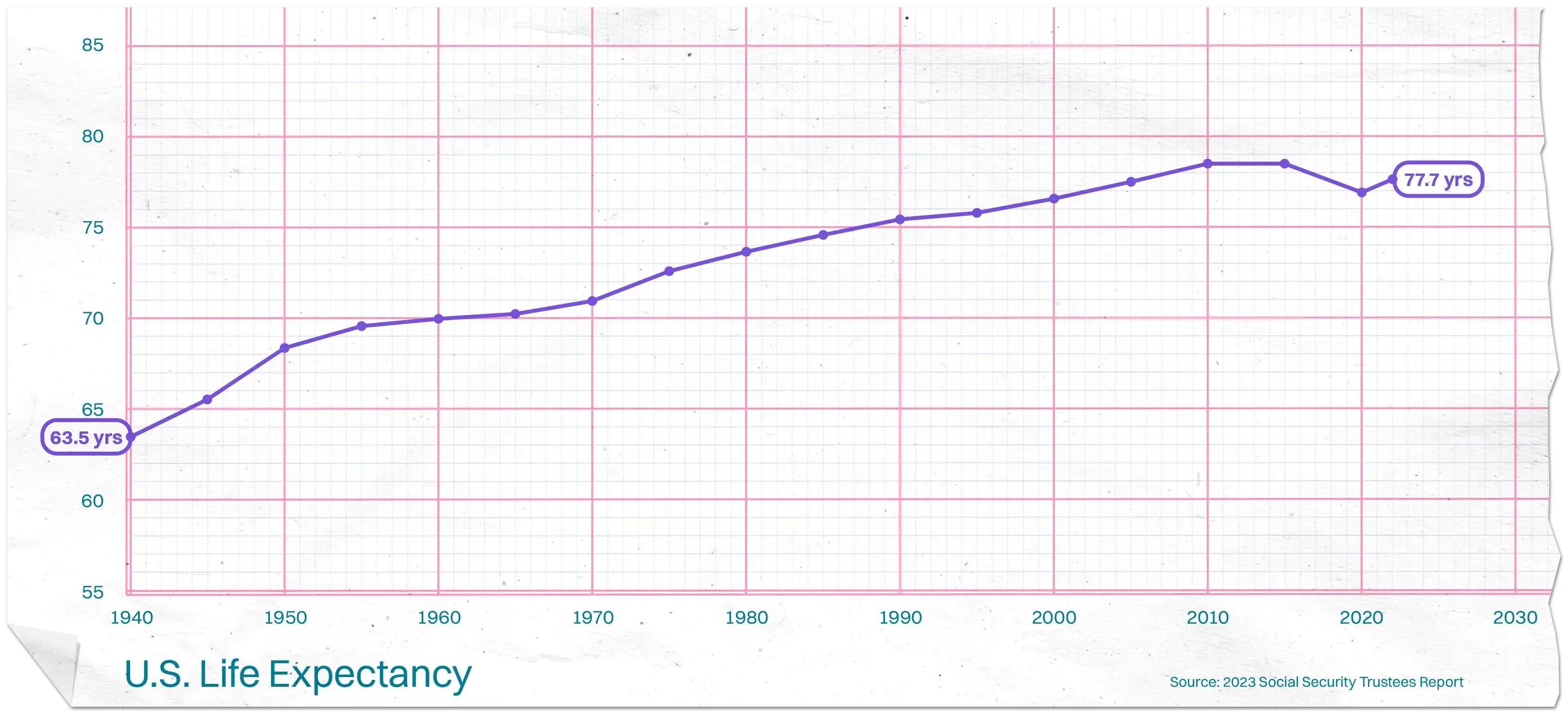

The result is a massive increase in the number of Americans reaching retirement age. And those Americans are living longer.

In the United States, a man who reaches his 65th birthday can expect to live until he’s 82.5 years old. The life expectancy for women is even higher; if a woman reaches 65, she can expect to live until she’s 85 years old.

America’s aging population presents Social Security with two challenges:

- The program is experiencing a huge increase in the number of beneficiaries, and

- Those beneficiaries will live longer - and collect benefits longer - than any group of retirees in history.

Lower Birth Rates, Fewer Workers

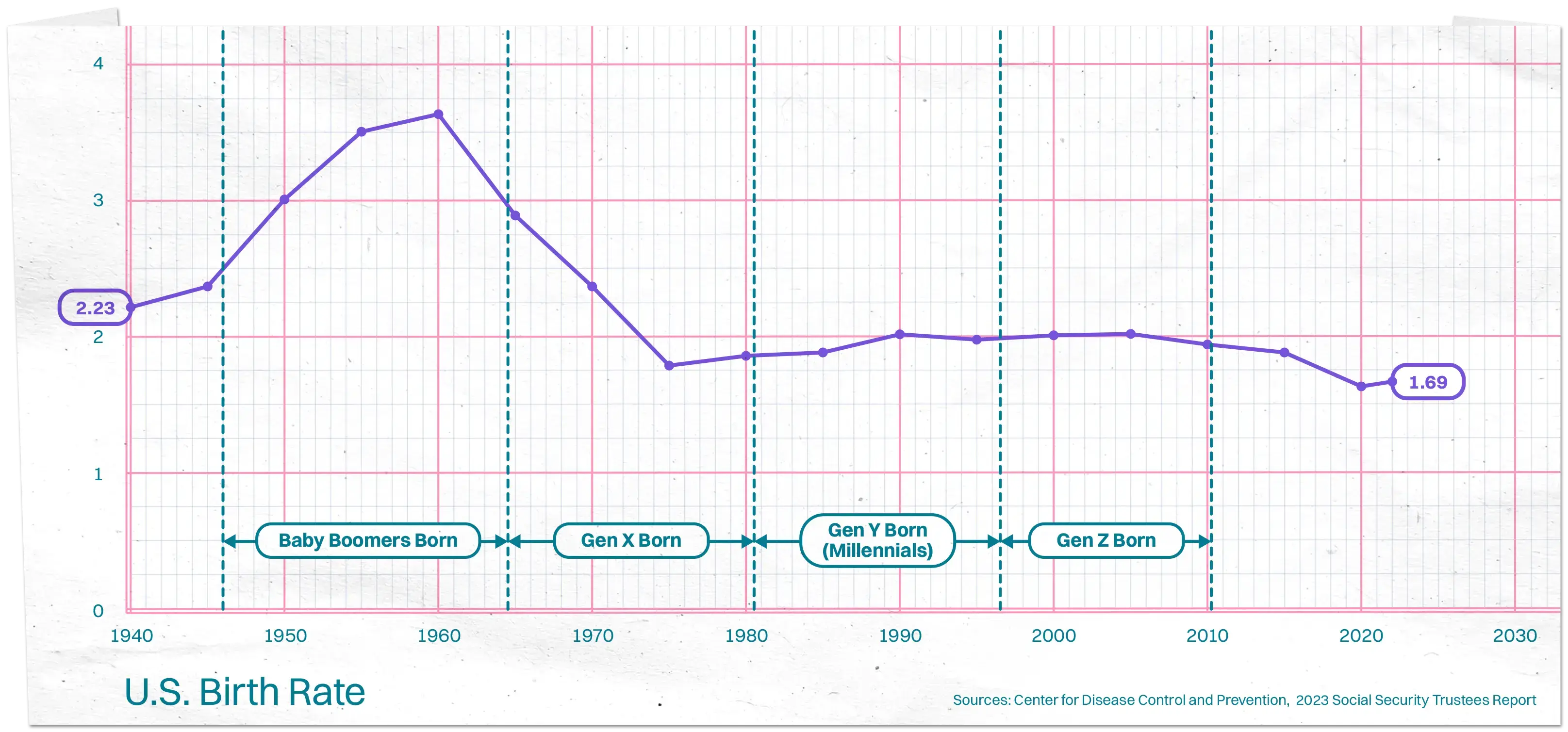

Meanwhile, there are fewer workers paying into the Social Security program. This is the result of declining birth rates in the United States, which dropped sharply following the 1950s baby boom.

In recent years, the United States' birth rate has been so low that it's actually failed to reach what’s known as the “replacement” fertility level. To maintain the current size of the U.S. population, we need an average of 2.1 births per woman in the United States. In 2023, the average was only 1.6. Our shrinking population means that as Baby Boomers retire, there aren’t enough workers to replace them. So while the pool of retirees is growing, the group of young American workers paying taxes is shrinking in proportion.

Key Ratio: Workers to Beneficiaries

These demographic trends - lower birth rates, more retirees, and longer life expectancies - have created an imbalance in the ratio of workers to retirees. And that’s a problem for Social Security.

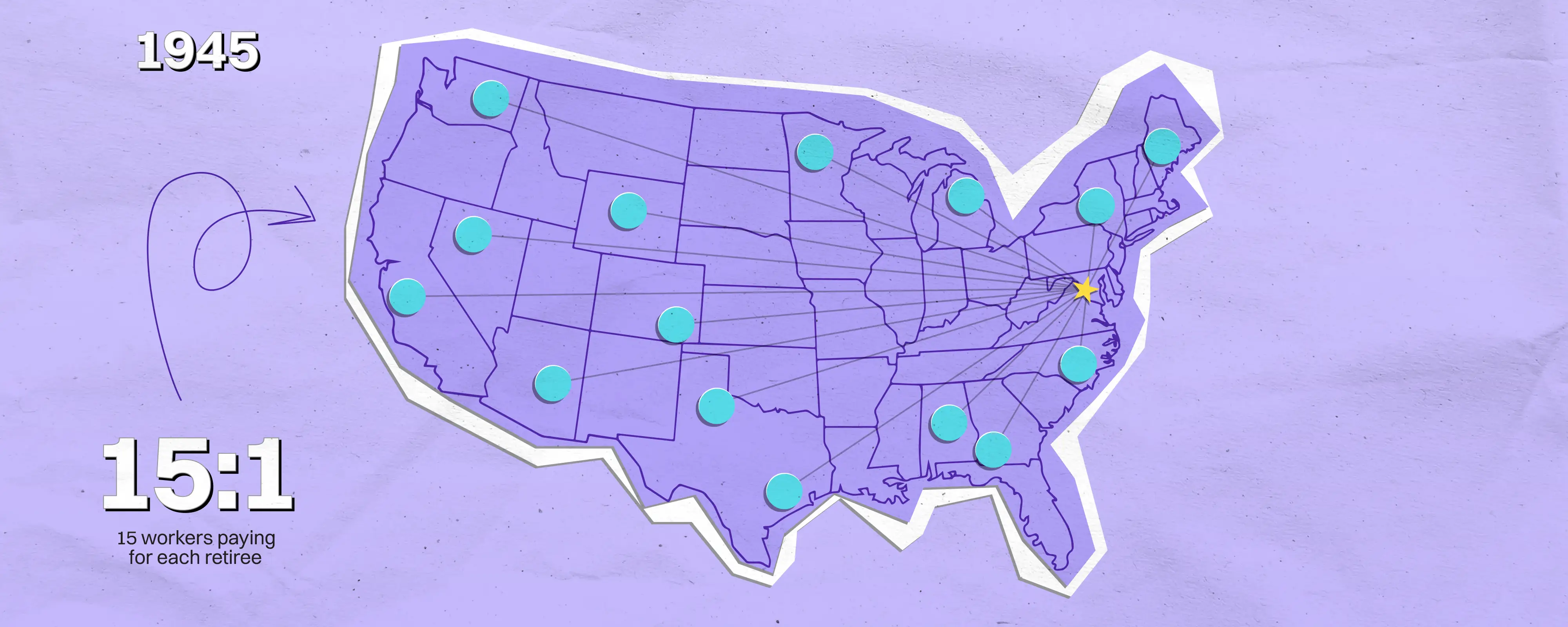

In 1945, there were 15 workers paying into the system for each retiree collecting benefits.

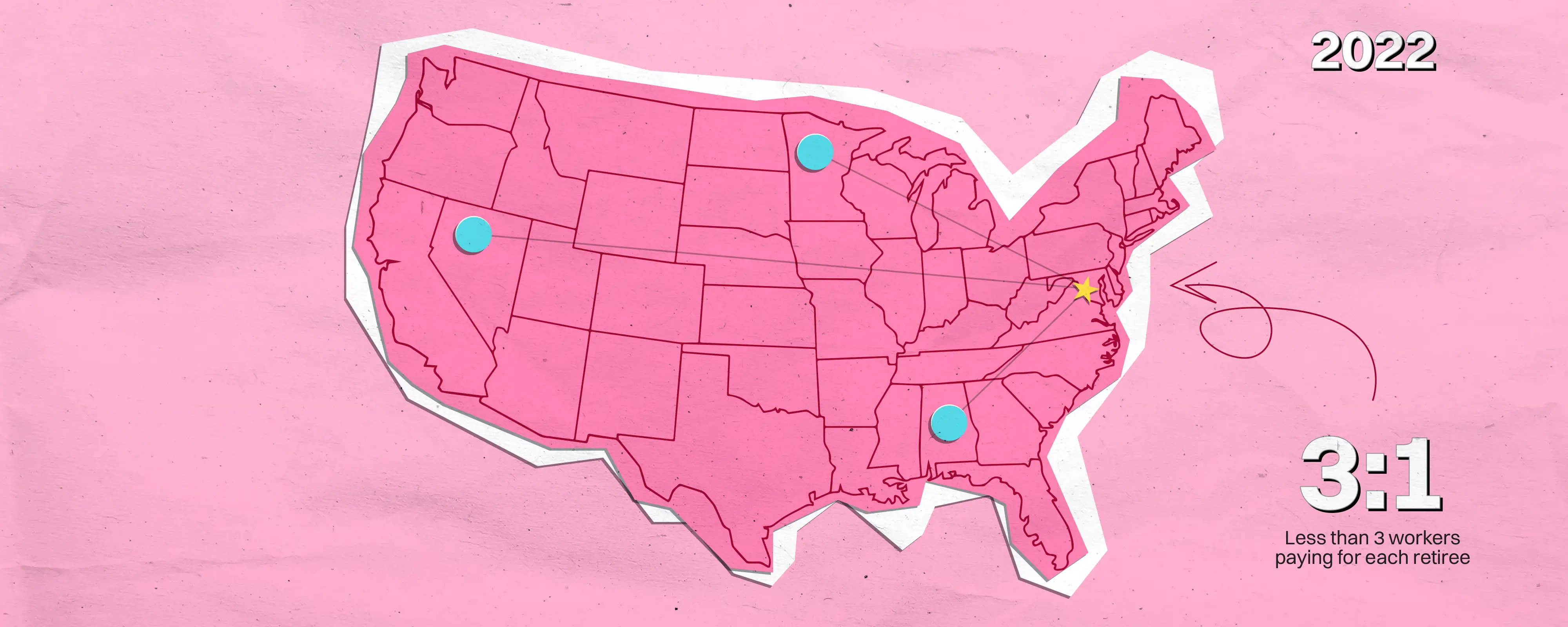

In 2022, there were fewer than 3 workers for each retiree.

LESS REVENUE, SHRINKING TRUST FUND

You might be wondering how fewer workers are able to support the benefits of a growing pool of retirees. The short answer is they aren’t.

For most of its history, Social Security has been able to collect enough revenue to pay out the benefits it’s promised retirees. In fact, it’s even experienced periods of surplus, where it took in more money than it needed to send out.

In leaner times, when payroll taxes haven’t been able to cover the total cost of benefits, we’ve used the money from those surpluses to fill the gap. And that’s what we’re doing today.

In 2010, Social Security began sending out more money in benefit checks than it took in through the payroll tax. In 2022, program benefits cost $1.48 trillion, leaving us with a shortfall of $150 billion.

KEY DATE: 2033

So why hasn’t Social Security been declared insolvent already?

Well, we’re essentially plugging the hole with money left over from the last period of surplus. But the Social Security Trustees estimate that we’ll run out of surplus money in 2033. And from that point on, projections indicate the program will face deep deficits.

.svg)